Faults in Fall Part 1

I know this may seem pretty basic, but I want anyone who reads future posts to have the basic geology knowledge to be able to follow along. As most of the landscapes you see are the work of faulting (that and erosion), I figured this would be a good starting point. As I move along with these short lessons, I’ll slowly add to the depth of explanation, as well as provide real life examples that you can visit.

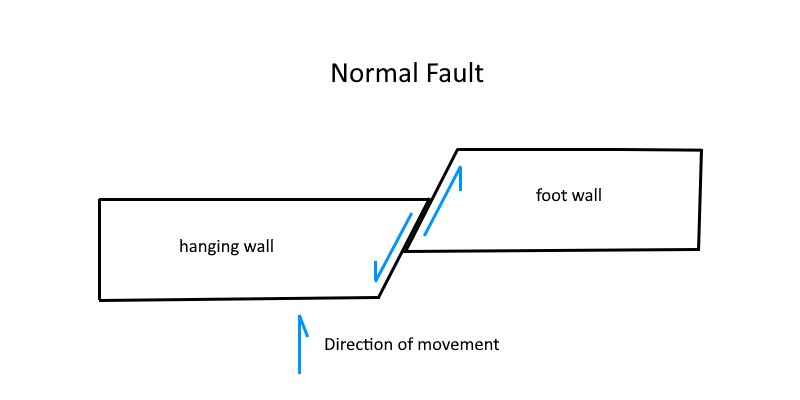

Normal Faults

Normal faults occur when there is crustal extension, where the Earth’s crust is being pulled apart. There are many areas in the US that have great examples of normal faults, especially the Basin and Range region (parts of Idaho, Oregon, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, California, Arizona and New Mexico). In normal faulting, there are two blocks that are moving in opposite directions vertically. When the overhanging block, also know as the hanging wall, is moving downwards in relation to the block underneath it, also known as the foot wall, you have a normal fault (Fig. 1).

Where to see normal faults

- Grand Teton National Park

- Death Valley National Park

- Great Sand Dunes National Park

Reverse Faults

Reverse faults occur where the crust is getting shorter, also known as crustal compression, and examples abound in the American West. Since they tend to form in the cores of mountain ranges as they are uplifted, they generally don’t make a visible appearance on the surface (thrust faults do, that’s for a later post). Road cuts through most ranges of the West will often times expose them, but unless there are visible strata that can be traced, they are difficult to see. The concept is pretty simple, the hanging wall( the block that overhangs the other), slides up in relation to the foot wall (Fig. 2).

As I said, reverse faults form where the earth’s crust is being shortened or compressed. I couldn’t find any real good examples of basic reverse faulting in my photos, but in one of my next posts, you’ll get to see their relatives, the thrust fault.

Places to See Reverse Faults

- Pretty much any mountain range, or rocks from a prehistoric mountain range. Some of the ranges of the West were partially or wholly lifted by reverse faulting(many other factors involved, but its one of the primary mechanisms for uplift). They tend to be more visible in sedimentary rocks, as its easier to trace the fault movement.

Next time we will talk about the cousins of these two, detachment and thrust faults. Don’t forget to Tag Along!

References

- Roadside Geology of Wyoming, D. Lageson and D. Spearing

- Roadside Geology of Nevada, F. Decourten and N. Biggar

- The Science Teaching Staff at BOMUSD