Thrust, Detachment, and Listric Faults

Thrust and detachment faults are just simple relatives of each type of fault discussed in the last fault post, reverse and normal faults, respectively. Listric faults are the connections between a normal fault, and where it curves at depth to a flatter angle, merging with a detachment fault.

Thrust Faults

Just like any other reverse fault, they form due to crustal compression or shortening. What makes them different from a regular reverse fault is the angle, if the angle of the fault plane is less than 45 degrees, its considered a thrust fault (Fig. 1 & Fig. 2).

Where to see thrust faults

- Rocky Mountains (Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah)

- The Alps

Detachment Faults

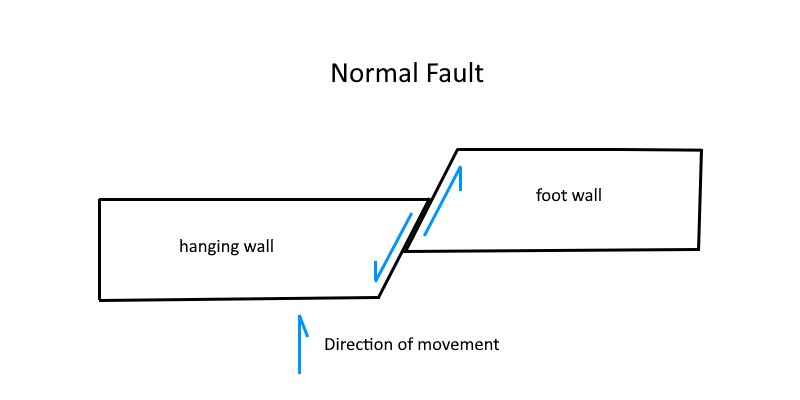

Basically, a detachment fault is when a block slides at a low angle down and off of another block, a normal fault at a real low angle. Below is a diagram of a regular normal fault (Fig. 3), a detachment fault (Fig. 4) is at a much shallower angle, sometimes being within a few degrees of flat. They are generally caused by crustal extension, and can either occur over geologic time or very quickly.

Places to see detachment faults

- Sevier Desert, Utah (can’t actually see it haha!)

- Metamorphic Core Complexes of the Northern Rockies (Idaho, Montana)

- Heart Mountain Detachment Fault, Bighorn Basin, WY

Listric Faults

Listric Faults are the curving connectors between normal faults at the surface and detachment faults at depth (Fig. 5). They are found in areas where large sections of the earth’s crust are being rifted, or stretched apart. Because they are at depth, their structure and shape is known from seismic surveys and well drilling (oil, gas, and water).

References

- Roadside Geology of Nevada, F. DeCourten and N. Biggar

- Roadside Geology of Utah, L. Chronic and H. Chronic

- Roadside Geology of Colorado, F. Williams and H. Chronic

1 thought on “Faults in Fall Part 2”